Most of the people know about the so-called “Parameter Sniffing”. This topic was discussed in many aspects in a number of great articles. It is interesting that not only parameters might be “sniffed” during the first execution, but also a runtime constant functions. Let’s look at the example.

Test Data

I will use a test server and administrator account to run the script below, be sure you have enough privileges on your test server if you want to try out the script below.

At first, we will create a database and two users.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 |

-- 1. Create database create database RtConst; go alter database RtConst set compatibility_level = 110; go use RtConst; go -- 2. Create users create login user1 with password = '123', check_policy = off; create login user2 with password = '123', check_policy = off; create user user1 for login user1; create user user2 for login user2; grant select, showplan to user1; grant select, showplan to user2; go |

Now, assume we have a kind of log in our system implemented with the table below, and the non-clustered index on the user field in that table.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 |

-- 3. Create table Log and fill with data create table dbo.ActionLog( ActionDate datetime not null, ActionUser sysname not null, ActionData varchar(1000) not null, primary key(ActionDate, ActionUser) ); create index ix_ActionUser on dbo.ActionLog(ActionUser); go |

It is common enough that each user may have different amount of activities and different amount of log records. For the demonstration, let’s create only two users, the first one has 10 logged actions, the second one much more.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 |

-- 10 000 numbers with nums(n) as ( select top(10000) row_number() over(order by(select null)) from master..spt_values v1,master..spt_values v2 ) insert dbo.ActionLog(ActionDate, ActionUser, ActionData) select ActionDate = dateadd (mi, n, '20150101'), -- Some date ActionUser = case when n%1000 = 0 then N'user1' else N'user2' end, -- 10 actions from user1, 9990 actions fro user2 ActionData = 'Some Action '+convert(varchar(10),n) -- SOme action data from nums ; go |

Now let’s query the table for the user actions and examine the plans and IO stats.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

-- 4. Check for the plans set statistics xml, io on; select * from dbo.ActionLog where ActionUser = N'user1'; select * from dbo.ActionLog where ActionUser = N'user2'; set statistics xml, io off; go |

For the user with the small number of entries, the “Index Seek + Lookup” strategy is a better choice. It is cheaper to seek the non-covering non-clustered index and then look up the rest of data using clustered index.

For the second query, it is cheaper to scan the clustered index because the query touches much more rows.

The IO statistics for those queries are:

Runtime Constant Function Sniffing

Imagine, that we have the query in our system that displays log actions for the current user and implemented as follows.

|

1 |

select * from dbo.ActionLog where ActionUser = suser_sname(); |

Let’s run exactly the same query first under user1, then under user2 and gather IO stats and plans.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 |

-- 5. Sniffed RT const dbcc freeproccache -- Warning cache free; go set statistics xml, io on; go execute as login = 'user1'; go select * from dbo.ActionLog where ActionUser = suser_sname(); go revert; go execute as login = 'user2'; go select * from dbo.ActionLog where ActionUser = suser_sname(); go revert; go set statistics xml, io off; go |

The plans would be the same for both users, even for the second user it is better to use Clustered Index Scan strategy.

That means the IO stats for the second query is not good.

Let’s clear cache and replay this example in reverse order. First execute as user2 and then as user1.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 |

-- 6. Opposite way dbcc freeproccache;-- Warning cache free; go set statistics xml, io on; go execute as login = 'user2'; go select * from dbo.ActionLog where ActionUser = suser_sname(); go revert; go execute as login = 'user1'; go select * from dbo.ActionLog where ActionUser = suser_sname(); go revert; go set statistics xml, io off; go |

Both plans now are Clustered Index Scans and have 63 Logical reads, even the plan for the user1.

If you stop for a moment and think about it, you may notice that this behavior is very similar to the “Parameter Sniffing” behavior, with the exception, that we have no parameters here. Like in the “parameter sniffing” pattern, the plan behaves of the value that is used to build a plan during the first execution. The value that had an intrinsic function during the first execution.

Runtime Constant Functions

For some of scalar functions, SQL Server pulls out the function expression from the operator’s tree, caches it and reuses it during the query execution. For example, if you issue the query «select sysdatetime(), sysdatetime()» you will get exactly the same time in both columns up to 10^-6 seconds. If the function was really invoked two times during the execution, then obviously, because it is not deterministic, the time for one of the columns should be slightly different from the other. That does not happen, because the function expression is extracted and executed only once during the execution. I will refer you to the Connor’s Cunningham blog post Conor vs. Runtime Constant Functions for more details.

Interesting part is that this expression extraction happens during the plan compilation, and the value is sniffed, as well as parameter in a module, during the first execution.

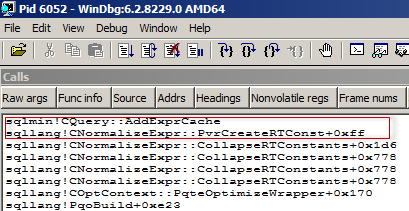

We may observe this behavior with attaching debugger, setting break point on sqlmin!CQuery::AddExprCachemethod and running two queries.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 |

go dbcc freeproccache;-- Warning cache free; go declare @user sysname = N'someuser'; select * from dbo.ActionLog where ActionUser = @user; go dbcc freeproccache;-- Warning cache free; go select * from dbo.ActionLog where ActionUser = suser_sname(); go |

The first one query returns immediately because there is no breakpoint hit because there is nothing to cache. The second one will hit the breakpoint on the stage of creating runtime constant (sqllang!CNormalizeExpr::PvrCreateRTConst), and caching it (sqlmin!CQuery::AddExprCache), we will observe the following call stack in WinDbg.

Another example

Now let’s imagine that you have some kind of order management system and want to know the orders that were created during the last hour from now. For that purpose, we may write the query like this.

|

1 |

select * from dbo.Orders where OrderDate >= dateadd(hh,-1, getdate()) and OrderDate < getdate(); |

If you issue this query first time, at the moment when there are very few orders, you will likely get the plan with Index Seek + Lookup strategy. If during the day there will be some kind of a “rush hour” (say very few orders in the morning and a lot of orders in the evening), SQL Server will still use the cached plan for the small amount of orders, of course unless adding new orders won’t trigger update statistics and the plan would be recompiled. However, that might not happen immediately.

For the demo purpose, not to wait one hour we will make the time window very small, let’s wait for 10 seconds. Also, we will add the future orders beforehand with the date – now + 10 seconds – that is not to create a big table, because adding the orders to the small table will exceed 20% percent statistics threshold and trigger update statistics and recompilation, so we will not observe the cached expression effect.

At the first step, we will run and compile the query for the time window [now-10 sec; now]. At that moment, only 10 orders fit this window. Then we will wait for 10 seconds and re-run the query, but this time the order amount is bigger (pretending a lot of orders were created during that time). As a final step, we will manually trigger recompilation by the procedure sp_recompile, to see what the efficient plan should be.

Let’s run the whole script at once.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 |

-- 7. Another example if object_id('dbo.Orders') is not null drop table dbo.Orders; create table dbo.Orders( OrderID int identity primary key, OrderDate datetime not null, OrderData varchar(1000) not null ); create index ix_OrderDate on dbo.Orders (OrderDate); go with nums(n) as ( select top(10000) row_number() over(order by(select null)) from master..spt_values v1,master..spt_values v2 ) insert dbo.Orders(OrderDate, OrderData) select OrderDate = dateadd(ss, case when n <= 10 then 1 else 10 end, getdate()), OrderData = 'Some Data' from nums ; go update statistics dbo.Orders with fullscan; go waitfor delay '00:00:01'; go set statistics xml, io on; select * from dbo.Orders where OrderDate >= dateadd(ss,-10, getdate()) and OrderDate < getdate(); set statistics xml, io off; go waitfor delay '00:00:10'; go set statistics xml, io on; select * from dbo.Orders where OrderDate >= dateadd(ss,-10, getdate()) and OrderDate < getdate(); set statistics xml, io off; go sp_recompile 'dbo.Orders'; go set statistics xml, io on; select * from dbo.Orders where OrderDate >= dateadd(ss,-10, getdate()) and OrderDate < getdate(); set statistics xml, io off; go |

Both plans using Seek + Lookup pattern, and the reads are not good for the second query. The third plan, after recompilation, uses Scan and the reads are ok.

SQL Server Version

As you may have noticed on the database creation step I set the compatibility level to 110 (SQL Server 2012), that is done to force old cardinality estimation (CE) behavior. The first example (with the log table) in case of the new CE will produce scans both times. The expression is still cached, but the new CE will estimate the number of rows using density (like it is doing in case of the optimize for unknown hint). While the second example does not depend on the CE version.

Conclusion

Though the queries and situations presented here are artificial, I think, it is useful to know what kind of SQL Server behavior. For curiosity TF 4136 (disabling parameter sniffing) or optimize for unknown – gives no effect on this behavior. That is because different classes are responsible for handling parameters and runtime constant functions internally. If this kind of “sniffing” becomes a problem – you may replace the direct call of the intrinsic function by the variable, and then treat the situation as you normally do with variables or parameters.

That’s all, thanks for reading.

See more

Check out ApexSQL Plan, to view SQL execution plans, including comparing plans, stored procedure performance profiling, missing index details, lazy profiling, wait times, plan execution history and more

- SQL Server 2017: Adaptive Join Internals - April 30, 2018

- SQL Server 2017: How to Get a Parallel Plan - April 28, 2018

- SQL Server 2017: Statistics to Compile a Query Plan - April 28, 2018