One big component of DevSecOps surrounding security testing involves how we build and deploy with shared information access of details that may be valuable to an attacker. In order to understand these risks, we must think like attacker who wants to compromise an environment that is focusing on quickly writing code, building the code, testing it, and deploying it across multiple environments. An attacker’s ultimate target will be the highest environment – often a production environment, but some attackers may target lower environments because they may be able to inject code that is deployed to production. In addition, an attacker may only be trying to learn about how an environment is laid out to attack in other ways, such as using social engineering with key information.

A Lesson From Duqu

Duqu and Duqu 2.0 were two of the most sophisticated attacks we’ve seen in the past decade. One of the behaviors of the first version, Duqu, involved creating blank images and sending messages through these blank images. If you consider this design combined with any “temporary data” you can imagine how easy these techniques could bypass any security testing we may run to check for abnormal behavior.

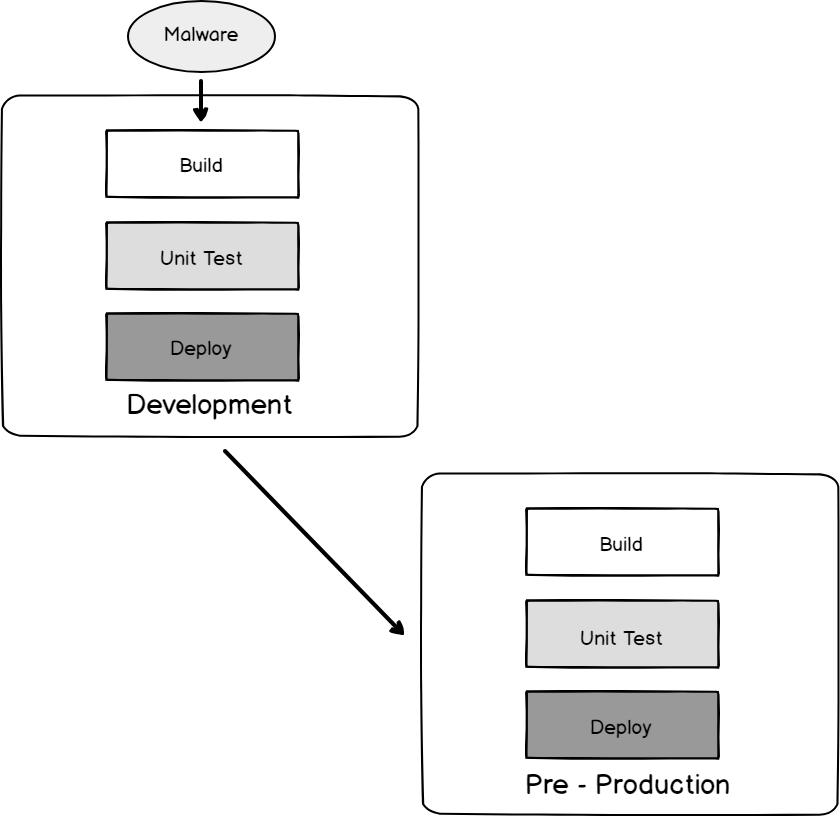

While Duqu used zero days to compromise the system, unfortunately it gives attackers ideas about how to compromise systems and one technique to combine with a Duqu-like attack is to use a software lifecycle against companies. If attackers can target lower environments with code injection, that code injection will pass to higher environments if undetected. We may have security testing that checks for this in some environments (such as lower), but depending on our configurations and where we store these configurations, an attacker may know this and place dormant code or executions where it won’t be tested.

If an attacker can determine how development is deployed through production, the attacker may be able to use the software lifecycle against the company.

Even if an attacker is not able to compromise deployment security by injecting code, the attacker may be able to identify key pieces of information about the target’s environment or design that could be useful in other attacks, such as social engineering by presenting as an employee. When we consider security testing, it’s easy to overlook the social engineering side and key pieces of information from our environment can make this easier for attackers because they will appear to be employees at our company, or people deeply informed about our company’s architecture.

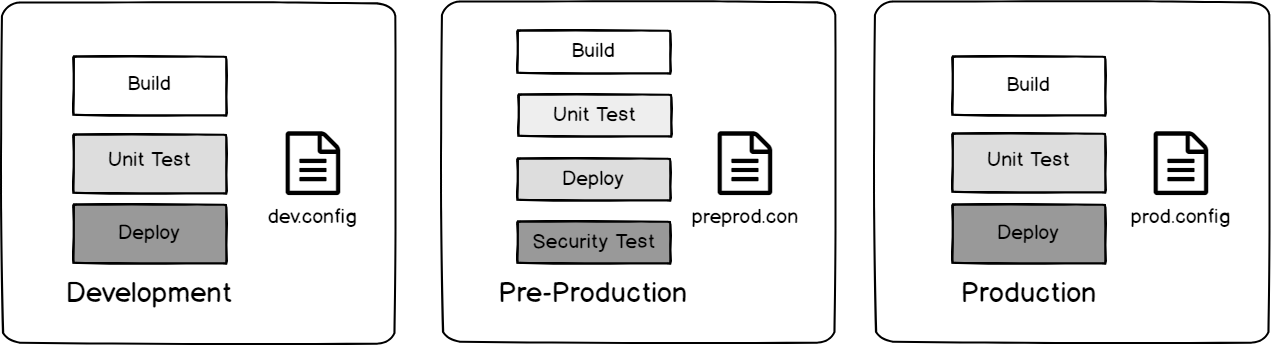

For these reasons, we should consider this with security testing and how we create upper environments from lower environments in the context of DevSecOps:

- Build and deploy process. We do not want unauthorized individuals understanding the details of how changes in development are deployed through production. Like we shouldn’t assign higher permissions across the board with all developers, we should not reveal this information to most developers. Some companies may have penetration testing between environment deployments, or some environments may only test one of the many environments. Attackers can inject code that may do “nothing” in some environments (dynamic) to get around our security testing – why revelation can be costly

- Shared information. If an attacker knows key details about our environment, the attack becomes easier. For this reason, we have to be extremely careful about sharing information among employees. Even what we may think of as “simple details” like our configuration file naming convention or our server names can be incredibly useful to an attacker to circumvent our security testing

We’ll look at these two in more depth: being strict with both our deployment strategy and any information we use dynamically for each environment, such as variables or shared details.

Our Build and Deploy Process

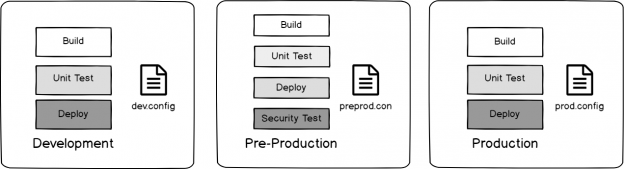

We’ll look at the below image from the viewpoint of an attacker: we know that security testing occurs in pre-production, but does not occur in development or production and we also know each environment uses its own configuration file. If we wanted to inject code, but skip an environment using the config, which environment would we skip?

Our build and deploy design for our each of our three environments.

We know the answer is pre-production – it’s running tests for a possible attack, whereas the other two environments are not. Also, to bypass the security testing, we can use the configuration file based on this design by attacking the dev.config and prod.config files. The purpose of this exercise is to think like an attacker and imagine how an attacker might use our design against us.

How easy is this information to access? In addition, how many of our developers know this is our design? Even with appropriate high-level developers, are there ways where this design could be compromised – such as shoulder surfing at a remote location? These are considerations for how we create our design and how we think about who should have access.

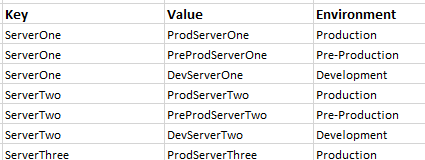

Shared Access of Key Information

In some cases, companies may use deployment tools with information or variables that store information about all the environments from development to production. For an example, suppose that we have 3 environments of development, preproduction and production and we manage 20 database servers in each environment. One technique for dynamically using the values based on environments is using a key-value type storage technique where we use the appropriate value for the key based on the environment – using the below image, if we’re adding ServerOne to a connection string for Production, it would be ProdServerOne and if it was another environment, it would automatically pick up the value. Some do this with spreadsheets (shown in the below image) and other use tools that have derivatives of this and these allow convenient and fast deployments – an alternative example of maintaining separate configs per environment instead of dynamic switching could cost more on the development side.

A popular technique that allows to use the appropriate key value based on the environment.

Because spreadsheets like this or some deployment tools can store detailed information about our environments from the servers to the configuration to the database, they can become targets for attackers. To an attacker, a spreadsheet or deployment tool with this information is like a map that can also show where and how to possibly make an attack from code injection to social engineering. In addition, when we think of security testing, we may overlook deployment spreadsheets or tools such as these since we’re fundamentally using them to conveniently deploy changes across our environments.

We should be aware of the risks of tools like these and how we use them. While it’s understandable that we want fast and convenient deployments with environments that mirror each other as close as possible, it may not be wise to allow developers to access these shared of information even if it makes their troubleshooting quick. We may also want to consider if we want some of a development team to have access, or allow access to only lower environments. For security testing, it’s not only the software, but the tools we may use that create our software that we should consider.

Principles to Reduce Risks

As we consider security testing in the context of shared information for deployments, the below principles can help us prevent some of the compromises we’ve discussed.

- Relative to our security testing requirements, share the least amount of information required to complete a request. Because high-level information can (and often is) used in social engineering as “proof” of identity, very few people should know this information. We may consider managers of development teams appropriate, or we may consider some keys from our example as inappropriate to share

- If compatible with security testing requirements, whether custom or through a tool, maintain shared information separately by environment when developers need to have access to how lower environments function for debugging. This can achieve the balance of development convenience and development security – we want developers to do their work efficiently, but by reducing the risks of a compromise

- We must use extreme caution with shared information – whether spreadsheets or a tool – as a compromised computer with even appropriate access could result in the leak of information. When we talk about compromise here, it could be a compromise as simple as shoulder surfing, or an attack as complex as malware

- In rare situations, requiring strict security testing compatibility, use an inconvenient design that requires delay. Delay can be a strong security feature. Attackers know that urgency is one of the easiest ways to attack a company

Conclusion

In our security testing, under the umbrella of DevSecOps, we want to consider access to information that an attacker could use to compromise us further. Unfortunately, shared information that we use for dynamic deployments can sometimes contain this type of information – such as server names, config files names, etc. If compromised, this can result in a broad range of attacks from a technical attack like code injection to a non-technical attack like social engineering where the attacker appears to be an employee. We want to design for convenient deployments by providing developers what they need, while also keeping key information secure.

Table of contents

| DevSecOps: Developing with Automated Security Testing |

| DevSecOps: Security Testing Around Builds and Shared Information |

- Data Masking or Altering Behavioral Information - June 26, 2020

- Security Testing with extreme data volume ranges - June 19, 2020

- SQL Server performance tuning – RESOURCE_SEMAPHORE waits - June 16, 2020