Introduction

If you’ve been developing in SQL Server for any length of time, you’ve no doubt hit this scenario: You have an existing, working query that produces results your customers or business owners say are correct. Now, you’re asked to change something, or perhaps you find out your existing code will have to work with new source data or maybe there’s a performance problem and you need to tune the query. Whatever the case, you want to be sure that whatever changes have been made (whether in your code or somewhere else), the changes in the output are as expected. In other words, you need to be sure that anything that was supposed to change, did, and that anything else remains the same. So, how can you easily do that in SQL Server?

In short, I’m going to look at an efficient way to just identify differences and produce some helpful statistics along with them. Along the way, I hope you learn a few useful techniques.

Setting up a test environment

We’ll need two tables to test with, so here is some simple code that will do the trick:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 |

USE [SQLShack] GO /****** Object: Table [dbo].[Original] Script Date: 9/14/2017 7:57:37 PM ******/ SET ANSI_NULLS ON GO SET QUOTED_IDENTIFIER ON GO CREATE TABLE [dbo].[Original]( [CustId] [int] IDENTITY(1,1) NOT NULL, [CustName] [varchar](255) NOT NULL, [CustAddress] [varchar](255) NOT NULL, [CustPhone] [numeric](12, 0) NULL, PRIMARY KEY CLUSTERED ( [CustId] ASC )WITH (PAD_INDEX = OFF, STATISTICS_NORECOMPUTE = OFF, IGNORE_DUP_KEY = OFF, ALLOW_ROW_LOCKS = ON, ALLOW_PAGE_LOCKS = ON) ON [PRIMARY] ) ON [PRIMARY] GO /****** Object: Table [dbo].[Revised] Script Date: 9/14/2017 7:57:37 PM ******/ SET ANSI_NULLS ON GO SET QUOTED_IDENTIFIER ON GO CREATE TABLE [dbo].[Revised]( [CustId] [int] IDENTITY(1,1) NOT NULL, [CustName] [varchar](255) NOT NULL, [CustAddress] [varchar](255) NOT NULL, [CustPhone] [numeric](12, 0) NULL, PRIMARY KEY CLUSTERED ( [CustId] ASC )WITH (PAD_INDEX = OFF, STATISTICS_NORECOMPUTE = OFF, IGNORE_DUP_KEY = OFF, ALLOW_ROW_LOCKS = ON, ALLOW_PAGE_LOCKS = ON) ON [PRIMARY] ) ON [PRIMARY] GO -- Populate Original Table SET IDENTITY_INSERT [dbo].[Original] ON GO INSERT [dbo].[Original] ([CustId], [CustName], [CustAddress], [CustPhone]) VALUES (1, N'Salvador', N'1 Main Street North', CAST(76197081653 AS Numeric(12, 0))) INSERT [dbo].[Original] ([CustId], [CustName], [CustAddress], [CustPhone]) VALUES (2, N'Edward', N'142 Main Street West', CAST(80414444338 AS Numeric(12, 0))) INSERT [dbo].[Original] ([CustId], [CustName], [CustAddress], [CustPhone]) VALUES (3, N'Gilbert', N'51 Main Street East', CAST(23416310745 AS Numeric(12, 0))) INSERT [dbo].[Original] ([CustId], [CustName], [CustAddress], [CustPhone]) VALUES (4, N'Nicholas', N'7 Walnut Street', CAST(62051432934 AS Numeric(12, 0))) INSERT [dbo].[Original] ([CustId], [CustName], [CustAddress], [CustPhone]) VALUES (5, N'Jorge', N'176 Washington Street', CAST(58796383002 AS Numeric(12, 0))) INSERT [dbo].[Original] ([CustId], [CustName], [CustAddress], [CustPhone]) VALUES (6, N'Ernest', N'39 Main Street', CAST(461992109 AS Numeric(12, 0))) INSERT [dbo].[Original] ([CustId], [CustName], [CustAddress], [CustPhone]) VALUES (7, N'Stella', N'191 Church Street', CAST(78584836879 AS Numeric(12, 0))) INSERT [dbo].[Original] ([CustId], [CustName], [CustAddress], [CustPhone]) VALUES (8, N'Jerome', N'177 Elm Street', CAST(30235760533 AS Numeric(12, 0))) INSERT [dbo].[Original] ([CustId], [CustName], [CustAddress], [CustPhone]) VALUES (9, N'Ray', N'214 High Street', CAST(57288772686 AS Numeric(12, 0))) INSERT [dbo].[Original] ([CustId], [CustName], [CustAddress], [CustPhone]) VALUES (10, N'Lawrence', N'53 Main Street South', CAST(92544965861 AS Numeric(12, 0))) GO SET IDENTITY_INSERT [dbo].[Original] OFF GO -- Populate Revised Table SET IDENTITY_INSERT [dbo].[Revised] ON GO INSERT [dbo].[Revised] ([CustId], [CustName], [CustAddress], [CustPhone]) VALUES (1, N'Jerome', N'1 Main Street North', CAST(36096777923 AS Numeric(12, 0))) INSERT [dbo].[Revised] ([CustId], [CustName], [CustAddress], [CustPhone]) VALUES (2, N'Lawrence', N'53 Main Street South', CAST(73368786216 AS Numeric(12, 0))) INSERT [dbo].[Revised] ([CustId], [CustName], [CustAddress], [CustPhone]) VALUES (3, N'Ray', N'214 High Street', CAST(64765571087 AS Numeric(12, 0))) INSERT [dbo].[Revised] ([CustId], [CustName], [CustAddress], [CustPhone]) VALUES (4, N'Gilbert', N'177 Elm Street', CAST(4979477778 AS Numeric(12, 0))) INSERT [dbo].[Revised] ([CustId], [CustName], [CustAddress], [CustPhone]) VALUES (5, N'Jorge', N'7 Walnut Street', CAST(88842643373 AS Numeric(12, 0))) INSERT [dbo].[Revised] ([CustId], [CustName], [CustAddress], [CustPhone]) VALUES (6, N'Ernest', N'176 Washington Street', CAST(17153094018 AS Numeric(12, 0))) INSERT [dbo].[Revised] ([CustId], [CustName], [CustAddress], [CustPhone]) VALUES (7, N'Edward', N'142 Main Street West', CAST(66115434358 AS Numeric(12, 0))) INSERT [dbo].[Revised] ([CustId], [CustName], [CustAddress], [CustPhone]) VALUES (8, N'Stella', N'51 Main Street East', CAST(94093532159 AS Numeric(12, 0))) INSERT [dbo].[Revised] ([CustId], [CustName], [CustAddress], [CustPhone]) VALUES (9, N'Nicholas', N'191 Church Street', CAST(54482064421 AS Numeric(12, 0))) INSERT [dbo].[Revised] ([CustId], [CustName], [CustAddress], [CustPhone]) VALUES (10, N'Salvador', N'39 Main Street', CAST(94689656558 AS Numeric(12, 0))) GO SET IDENTITY_INSERT [dbo].[Revised] OFF GO |

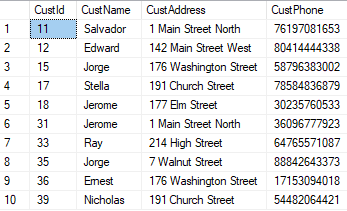

This code creates the tables Original and Revised that hold customer data. At the moment they are completely different, which you can see since they are small. But what if these tables had thousands or millions of rows? Eyeballing them wouldn’t be possible. You’d need a different approach. Enter set-based operations!

Set-based operations

If you remember your computer science classes, you’ll no doubt recall studying sets as mathematical objects. Relational databases combine set theory with relational calculus. Put them together and you get relational algebra, the foundation of all RDBMS’s (Thanks and hats-off to E.F. Codd). That means that we can use set theory. Remember these set operations?

A ∪ B Set union: Combine two sets into one

A ∩ B Set intersection: The members that A and B have in common

A − B Set difference: The members of A that are not in B

These have direct counterparts in SQL:

A ∪ B : UNION or UNION ALL (UNION eliminates duplicates, UNION ALL keeps them)

A ∩ B : INTERSECT

A − B : EXCEPT

We can use these to find out some things about our tables:

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

SELECT CustId, CustName, CustAddress, CustPhone FROM Original INTERSECT SELECT CustId, CustName, CustAddress, CustPhone FROM Revised |

Will show us what rows these two tables have in common (none, at the moment)

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

SELECT CustId, CustName, CustAddress, CustPhone FROM Original EXCEPT SELECT CustId, CustName, CustAddress, CustPhone FROM Revised |

Will show us all the rows of the Original table that are not in the Revised table (at the moment, that’s all of them).

Using these two queries, we can see if the tables are identical or what their differences may be. If the number of rows in the first query (INERSECT) is the same as the number of rows in the Original and Revised tables, they are identical, at least for tables having keys (since there can be no duplicates). Similarly, if the results from the second query (EXCEPT) are empty and the results from a similar query reversing the order of the selects is empty, they are equal. Saying it another way, if both sets have the same number of members and all members of one set are the same as all the members of the other set, they are equal.

Challenges with non-keyed tables

The tables we are working with are keyed so we know that each row must be unique in each table, since duplicate keys are not allowed. What about non-keyed tables? Here’s a simple example:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 |

DECLARE @t1 TABLE (a INT, b INT); INSERT INTO @t1 VALUES (1, 2), (1, 2), (2, 3), (3, 4); DECLARE @t2 TABLE (a INT, b INT); INSERT INTO @t2 VALUES (1, 2), (2, 3), (2, 3), (3, 4); SELECT * FROM @t1 EXCEPT SELECT * FROM @t2; |

The last query, using EXCEPT, returns an empty result. But the tables are different! The reason is that EXCEPT, INTERSECT and UNION eliminate duplicate rows. Now this query:

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

SELECT * FROM @t1 INTERSECT SELECT * FROM @t2; |

Returns 3 rows:

These are the three rows that the two tables have in common. However, since each table has 4 rows, you know they are not identical. Checking non-keyed tables for equality is a challenge I’ll leave for a future article.

Giving our tables something in common

Let’s go back to the first example using keyed tables. To make our comparisons interesting, let’s give our tables something in common:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 |

SET IDENTITY_INSERT Revised ON; INSERT INTO Revised(CustId, CustName, CustAddress, CustPhone) SELECT TOP 50 PERCENT CustId, CustName, CustAddress, CustPhone FROM Original ORDER BY NEWID(); SET IDENTITY_INSERT Revised OFF; |

Here, we take about half the rows of the Original table and insert them into the Revised table. Using ORDER BY NEWID() makes the selection pseudo-random.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 |

SET IDENTITY_INSERT Original ON; INSERT INTO Original(CustId, CustName, CustAddress, CustPhone) SELECT TOP 50 PERCENT CustId, CustName, CustAddress, CustPhone FROM Revised WHERE CustID NOT IN (SELECT CustId FROM Original) ORDER BY NEWID(); SET IDENTITY_INSERT Original OFF; |

This query takes some of the rows from the Revised table and inserts them into the Original table using a similar technique, while avoiding duplicates.

Now, the EXCEPT query is more interesting. Whichever table I put first, I should get 5 rows output. For example:

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

SELECT CustId, CustName, CustAddress, CustPhone FROM Revised EXCEPT SELECT CustId, CustName, CustAddress, CustPhone FROM Original |

Returns:

Now the two tables also have 10 rows in common:

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

SELECT CustId, CustName, CustAddress, CustPhone FROM Original INTERSECT SELECT CustId, CustName, CustAddress, CustPhone FROM Revised |

Returns:

Depending on the change being implemented, these results may be either good or bad. But at least now you have something to show for your efforts!

Row-to-row changes

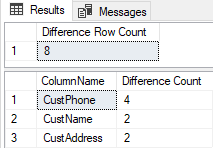

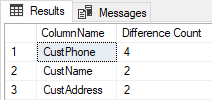

So far, we’ve only considered changes in whole rows. What if only certain columns are changing? For example, what if in the Revised table, for some customer id, the name or phone number changed? It would be great to be able to report the rows that changed and also to provide a summary of the number of changes by column and also some way to see what changed between two rows, not just visually, but programmatically. These sample tables are small and narrow. Imagine a table with 40 columns, not 4 and 1 million rows, not 10. Computing such a summary would be very tedious. I’m thinking about something like this:

This shows me that there are 8 rows with the same customer id but different contents and that four of them have different phone numbers, two have different names and two have different addresses.

I’ll also want to produce a table of these differences that can be joined back to the Original and Revised tables.

Checking comparability with sys.columns

Just because two tables look the same at first glance, that doesn’t mean that they are the same. To do the kind of comparison I’m talking about here, I need to be sure that really are the same. To that end I can use the system catalog view sys.columns. This view returns a row for each column of an object that has columns, such as views or tables. Each row contains the properties of a single column, e.g. the column name, datatype, and column_id. See the references section for a link to the official documentation where you can find all the details.

Now, there are at least two columns in sys.columns that will likely be different: object_id, which is the object id of the table or view to which the column belongs, and default_object_id, which is the id of a default object for that column, should one exist. There are other id columns that may be different as well. When using these techniques in your own work, check the ones that apply.

How can we use sys.columns to see if two tables have the same schema? Consider this query:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 |

SELECT * FROM sys.columns WHERE object_id = OBJECT_ID(N'Original') EXCEPT SELECT * FROM sys.columns WHERE object_id = OBJECT_ID(N'Revised'); |

If the two tables really are identical, the above query would return no results. However, we need to think about the columns that may differ because they refer to other objects. You can eliminate the problem this way:

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

IF object_id(N'tempdb..#Source', N'U') IS NOT NULL DROP TABLE #Source; SELECT TOP (0) * INTO #Source FROM sys.columns; |

This script will create a temporary table from sys.columns for the Original table. Note that the “SELECT INTO” in this snippet just copies the schema of sys.columns to a new, temporary table. Now, we can populate it like this:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

INSERT INTO #Source SELECT * FROM sys.columns c WHERE c.object_id = OBJECT_ID(N'Original') --AND c.is_identity = 0 |

I’ve commented out the check for an identity column. You might want to exclude identity columns since they are system generated and are likely to differ between otherwise-identical tables. In that case, you’ll want to match on the business keys, not the identity column. In the working example though, I explicitly set the customer ids so this does not apply, though it very well might in the next comparison. Now, so we don’t compare the columns that we know will be different:

|

1 2 3 |

ALTER TABLE #Source DROP COLUMN object_id, default_object_id, -- and possibly others |

Repeat the above logic for the target table (The Revised table in the working example). Then you can run:

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

SELECT * FROM #Source EXCEPT SELECT * FROM #Target; |

In the working example, this will return no results. (In case you are wondering, SELECT * is fine in this case because of the way the temporary tables are created – the schema and column order will be the same for any given release of SQL Server.) If the query does return results, you’ll have to take those differences into account. For the purpose of this article, however, I expect no results.

Creating differences

Starting with the Original and Revised tables, I’ll create some differences and leave some things the same:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 |

WITH MixUpCustName(CustId, CustName, CustAddress, CustPhone) AS ( SELECT TOP 50 PERCENT CustId, SUBSTRING(CustName,6, len(CustName)) + LEFT(CustName,5), CustAddress, CustPhone FROM Original ORDER BY NEWID() ), MixUpCustAddress(CustId, CustName, CustAddress, CustPhone) AS ( SELECT TOP 50 PERCENT CustId, CustName, SUBSTRING(CustAddress,6, len(CustAddress)) + LEFT(CustAddress,5), CustPhone FROM Original ORDER BY NEWID() ), MixUpCustPhone(CustId, CustName, CustAddress, CustPhone) AS ( SELECT TOP 50 PERCENT CustId, CustName, CustAddress, CAST(CustPhone / 100 AS int) + 42 FROM Original ORDER BY NEWID() ), MixItUp(CustId, CustName, CustAddress, CustPhone) AS ( SELECT CustId, CustName, CustAddress, CustPhone FROM MixUpCustName UNION SELECT CustId, CustName, CustAddress, CustPhone FROM MixUpCustAddress UNION SELECT CustId, CustName, CustAddress, CustPhone FROM MixUpCustPhone ) -- Main query to mix up the data UPDATE Revised SET Revised.CustName = MixItUp.CustName, Revised.CustAddress = MixItUp.CustAddress, Revised.CustPhone = MixItUp.CustPhone FROM Revised JOIN MixItUp ON Revised.CustId = MixItUp.CustId |

This query mixes up the data in the columns of the Revised table in randomly-selected rows by simple transpositions and arithmetic. I use ORDER BY NEWID() again to perform pseudo-random selection.

Computing basic statistics

Now that we know the tables are comparable, we can easily compare them to produce some basic difference statistics. For example:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 |

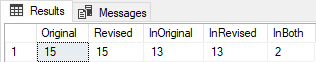

WITH InOriginal AS ( SELECT * FROM Original EXCEPT SELECT * FROM Revised ), InRevised AS ( SELECT * FROM Revised EXCEPT SELECT * FROM Original ), InBoth AS ( SELECT * FROM Revised INTERSECT SELECT * from Original ) SELECT (SELECT COUNT(*) FROM Original) AS Original, (SELECT COUNT(*) FROM Revised) AS Revised, (SELECT COUNT(*) FROM InOriginal) AS InOriginal, (SELECT COUNT(*) FROM InRevised) AS InRevised, (SELECT COUNT(*) FROM InBoth) AS InBoth; |

Returns:

for the working example. However, I want to go deeper!

Using SELECT … EXCEPT to find column differences

Since SQL uses three-value logic (True, False and Null), you might have written something like this to compare two columns:

|

1 2 3 4 |

WHERE a.col <> b.col OR a.col IS NULL AND b.col IS NOT NULL OR a.col IS NOT NULL and b.col IS NULL |

To check if columns from two tables are different. This works of course, but here is a simpler way!

|

1 |

WHERE NOT EXISTS (SELECT a.col EXCEPT SELECT b.col) |

This is much easier to write, is DRYer (DRY = Don’t Repeat Yourself) and takes care of the complicated logic in the original WHERE clause. On top of that, this does not cause a performance problem or make for a suddenly-complicated execution plan. The reason is that the sub query is comparing columns from two rows that are being matched, as in a JOIN for example. You can use this technique anywhere you need a simple comparison and columns (or variables) are nullable.

Now, applying this to the working example, consider this query:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 |

IF OBJECT_ID(N'tempdb..#diffcols', N'U') IS NOT NULL DROP TABLE #diffcols; SELECT src.CustId, CONCAT( IIF(EXISTS(SELECT src.CustId EXCEPT SELECT tgt.CustId ), RTRIM(', CustId '), ''), IIF(EXISTS(SELECT src.CustName EXCEPT SELECT tgt.CustName ), RTRIM(', CustName '), ''), IIF(EXISTS(SELECT src.CustAddress EXCEPT SELECT tgt.CustAddress ), RTRIM(', CustAddress '), ''), IIF(EXISTS(SELECT src.CustPhone EXCEPT SELECT tgt.CustPhone ), RTRIM(', CustPhone '), '')) + ', ' AS cols INTO #diffcols FROM Original src JOIN Revised tgt ON src.CustId = tgt.CustId WHERE EXISTS (SELECT src.* EXCEPT SELECT tgt.*) ; |

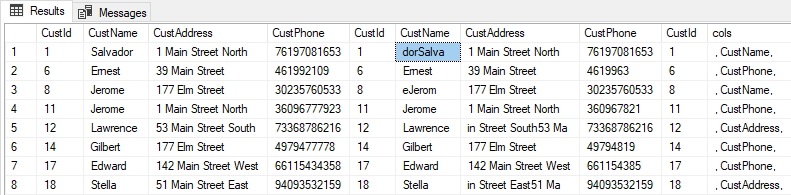

At its heart, this query joins the Original and Revised tables on customer id. For each pair of rows joined, the query returns a new column (called ‘cols’) that contains a concatenated list of column names if the columns differ. The query uses the technique just described to make things compact and easy to read. Since the query creates a new temporary table, let’s look at the contents:

The eight rows that differ, differ in specific columns. For each row that differs, we have a CSV list of column names. (The leading and trailing commas make it easy to pick out column names, both visually and programmatically). Although there is only one column listed for each customer id, there could be multiple columns listed and in a real-world scenario likely would be. Since the newly-created temp table has the customer id in it, you can easily do a three-way join between the Original and Revised tables to see the context and content of these changes, e.g.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

SELECT * FROM Original o JOIN Revised r ON o.CustId = r.CustId JOIN #diffcols d ON o.CustId = d.CustId |

Returns:

For a very-wide table, this makes it easy to zero in on the differences, since for each row, you have a neat list of the columns that differ and you can select them accordingly.

Generating detail difference statistics

There’s one other thing I can do with the temp table we just created. I can produce the table of differences I wanted. Here, I’m using those commas I inserted in the CSV column list to make it easy to search using a LIKE operator.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 |

WITH src AS ( SELECT SUM(IIF(d.cols LIKE '%, CustId, %' , 1, 0)) AS CustId, SUM(IIF(d.cols LIKE '%, CustName, %' , 1, 0)) AS CustName, SUM(IIF(d.cols LIKE '%, CustAddress, %' , 1, 0)) AS CustAddress, SUM(IIF(d.cols LIKE '%, CustPhone, %' , 1, 0)) AS CustPhone FROM #diffcols d ) SELECT ca.col AS ColumnName, ca.diff AS [Difference Count] FROM src CROSS APPLY ( VALUES ('CustId ',CustId ), ('CustName ',CustName ), ('CustAddress ',CustAddress ), ('CustPhone ',CustPhone ) ) ca(col, diff) WHERE diff > 0 ORDER BY diff desc ; |

This is an interesting query because I am not returning anything from the temp #diffcols table. Instead I use that table to create the sums of the differences then arrange the finally result using CROSS APPLY. You could do the same thing with UNPIVOT, but the CROSS APPLY VALUES syntax is shorter to write and easier on the eyes. Readability is always important, regardless of the language. There’s an interesting web site dedicated to writing obfuscated C. It’s interesting to see how much you can get done with a write-only program (one that you can’t read and make sense of). Don’t write obfuscated SQL, though!

This query returns:

Just what I wanted!

Creating a stored procedure to help

If you’ve been following along, you’ve probably already realized that this will be tedious to write for anything but a trivial example. Help is on the way! I’ve included a stored procedure that constructs the queries discussed in this article, using nothing more than the table names and a list of key columns to use for the join predicate, that you are free to use or modify to suit.

Summary

Comparing tables or query results is a necessary part of database development. Whether you are modifying an application that should change the result or making a change that should not change the result, you need tools to do this efficiently.

Downloads

References

- Codd, E. F. (1970). “A relational model of data for large shared data banks”

- sys.columns

- The International Obfuscated C Code Contest

- Snapshot Isolation in SQL Server - August 5, 2019

- Shrinking your database using DBCC SHRINKFILE - August 16, 2018

- Partial stored procedures in SQL Server - June 8, 2018