Non-Equi join in SQL Server sounds like something abstract (and fancy), but it’s not so abstract (and fancy) at all. The same stands for equi joins. After reading this article, I hope you’ll agree on that with me. Today’ I’ll try to explain what they are and when you should use them. So, let’s start.

Data Model

On this part, nothing has changed since the last article, so we’ll use the same model we’re using throughout this series.

If you’re still not familiar with it, take some time to see how the tables are related to each other. We’ll use only two tables from this model city and country, and we’ll comment on the data later in this article while taking a look at few non-equi join SQL Server queries. If you need to refresh your knowledge related to primary and foreign keys, select statement, and inner and left joins, this would be the right time to do it.

Equi-Joins vs. Non-Equi Joins in SQL Server

You’ve used equi-joins so far, and you’ve probably never called them that way. The reason for that is that they are so common, and the whole idea of databases is related to joining tables in such a manner. So, what are equi-joins? Equi-joins are standard joins where you’ll use the equality operator (=) while joining tables. Calling such “standard” joins an equi-joins is just a fancy way to name it. This stands for joins where you join using FK, but also for joins where you compare attributes that are not part of a foreign key (this is rarely used). Let’s examine this on a few examples.

We’ll start with something very familiar. First, we’ll list the contents of tables city and country and then use the INNER JOIN to combine only cities and countries that are related (logically, but also with the FK value). We could have done the same using LEFT JOIN or RIGHT JOIN too.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

SELECT * FROM city; SELECT * FROM country; SELECT * FROM city INNER JOIN country ON city.country_id = country.id; |

You can see the result of these 3 queries in the picture below.

Everything is as usual and as expected. All cities were joined to the counties they belong to. This is due to the fact we’ve joined tables on FK and used the equality sign in the join condition. So, this is an equi-join.

Now we’ll do the same using the non-equi join in SQL Server. First, we’ll join all cities and countries where the city doesn’t belong to that country. To do that, we’ll use the <> operator (you could have used the != operator too).

|

1 2 3 |

SELECT * FROM city INNER JOIN country ON city.country_id <> country.id; |

This result clearly shows what a non-equi join in SQL Server is. In this example, while joining tables, you won’t use the equality operator (=), but rather some other operator like <> or !=, >, >=, <, <=, BETWEEN … AND.

The point is that the operator used is a non-equality operator (any operator different than =).

In these two examples, we’ve joined two tables on their foreign keys. Still, that doesn’t have to be the case since we can join tables as we like (also on non-FK attributes). This stands for both equi joins, and non-equi joins in SQL Server. Still, this is a rare case, and you should be aware of why you’re doing that.

Non-Equi Joins in SQL Server – Examples

To explain non-equi joins in SQL Server better, we’ll go with a few more examples.

Let’s now write a query that shall return all possible pairs of cities (excluding a pair where we would have the same city twice). The query would look like this.

|

1 2 3 4 |

-- pairs of cities SELECT c2.id, c2.city_name, c1.id, c1.city_name FROM city c1 INNER JOIN city c2 ON c1.id <> c2.id; |

Please note that this query is a SELF JOIN because we’ve used the city table twice (and joined it to itself). Also, notice that we’ve used alias names (c1 and c2) to distinguish these two table instances. Such cases are rare, and you’ll mostly use them when you want to create categories/pairs/ 2D matrix for any business reason.

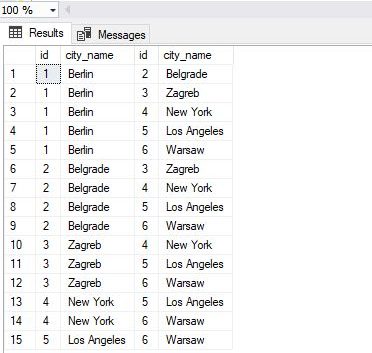

The result is shown in the picture below.

You can notice that we have 30 rows. We have 6 cities in our database. Since each city can be in a pair with 5 other cities (6 – that 1 city), that leads us to a total of 6 * 5 = 30 pairs. You can also notice that we have the same pair twice, with city names having switched positions in such pairs, e.g., Berlin – Belgrade & Belgrade – Berlin. For this example, that is OK, because we wanted exactly that.

A similar example would be creating a pair of teams in a league-style tournament for any sport, e.g., national football championship, where every single team will play exactly 2 matches again with any other team – one home match and one away match.

Other such pairs could be: pairs of persons from our database, pairs of cards from the card deck.

In the next example, we’ll have pairs of cities, but this time with each pair in the list appearing exactly one time.

|

1 2 3 4 |

-- pairs of cities (only once) SELECT c2.id, c2.city_name, c1.id, c1.city_name FROM city c1 INNER JOIN city c2 ON c1.id > c2.id; |

The query returns the following result.

As expected, this result set has 15 rows. This is due to the fact doubled pairs were eliminated using the > sign (each city is in pair only with cities having id greater than his id, so we don’t “go back” and examine previously generated pairs with lower id values). You can notice that now we have a pair Berlin – Belgrade, but not a pair Belgrade – Berlin. We could have achieved the same using the < sign. In that case, the order of pairs would be different.

When you join tables, either it’s equi join or non-equi join in SQL Server, you’ll mostly join these tables using a foreign key. Joining tables in such manner is the point of databases, after all. In most cases, it’s not rational (correct, wise, use whatever word you want) to relate tables using values from logically unrelated attributes. Still, if you, for any reason, want (need) to do that, you can do it. We’ll examine that in one example now.

|

1 2 3 |

SELECT * FROM city INNER JOIN country ON city.id <> country.id; |

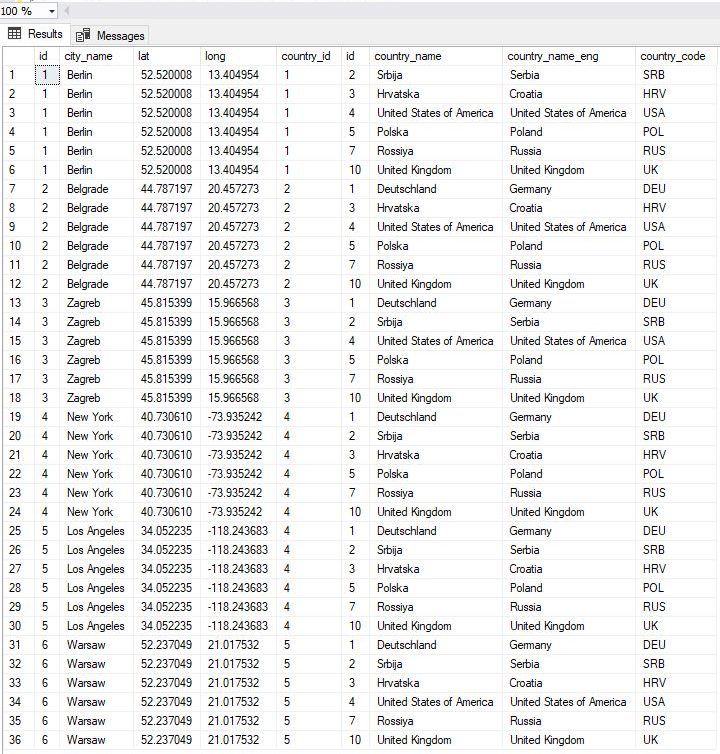

You can see the result in the picture below.

We’ve joined cities and countries which have different PK value. Since PK value is automatically generated and therefore is unique to our database, this result set is not related to the real world in any way. While the output itself is nothing meaningful, it proves the point that we can use non-equi join in SQL Server also on different tables.

When to use Non-Equi Joins in SQL Server?

You’ll use them:

-

When someone tells you so

I know this doesn’t explain anything, and this is more like a self-fulfilling prophecy, but mostly, you’ll use them when someone wants to test if you know what they are (school, college, job interview, etc.). Of course, this stands for anything else related to databases (or programming)

- When you need them, or they could ease your job a lot. OK, once more, this also stands for everything else, but for this bullet, we gave a few examples before. This mostly stands for generating categories and pairs combined with using self-join

- We haven’t mentioned it here, but you could also check for duplicate data (similar to self-join), compute running totals (there is a much better way to do that than using non-equi joins in SQL Server), or match against a range of values

Conclusion

I hope that today’s article gave a brief but clear explanation of what non-equi joins in SQL Server are and when you should use them. They are rarely used, so when you decide to go with them, use them wisely. And stay tuned for upcoming articles.

Table of contents

See more

Seamlessly integrate a powerful, SQL formatter into SSMS and/or Visual Studio with ApexSQL Refactor. ApexSQL Refactor is a SQL query formatter but it can also obfuscate SQL, refactor objects, safely rename objects and more – with nearly 200 customizable options

- Learn SQL: How to prevent SQL Injection attacks - May 17, 2021

- Learn SQL: Dynamic SQL - March 3, 2021

- Learn SQL: SQL Injection - November 2, 2020