In this article, we’ll look at using the built-in PWDCOMPARE function in SQL Server for security testing passwords. While this tool may seem like it exposes a weakness in Microsoft SQL Server because we can test for passwords, it should be of note that an attacker could do the same attack by attempting to login to our database server assuming the attacker was able to access a connection to it. Therefore, this function does not increase the risk of an attack on SQL Server but does help us identify possible weaknesses in our environment so that we can quickly mitigate these risks. In addition, we’ll also combine this with other related tools in SQL Server to help us with logins.

Understanding the function

For our security testing, we’ll look at the first two parameters – the actual password (“clear_text_password”) we want to test and the password hash (“password_hash”). Microsoft declared that they will be deprecating the third optional parameter of version, so we will not use this and it should be avoided since it will be removed in a later version of SQL Server. If the two parameters match, our output will result in a 1 whereas if they do not match, our output will result in a 0.

Creating logins for testing

Before security testing common passwords, we’ll create six logins with common password forms – some of these use name with numbers and some use the “password” with a number combination. Both of these are unfortunately common because they’re easy to memorize. First, we’ll check to ensure that none of these six logins exist – the below query should return 0 records:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 |

USE [master] SELECT [name] , [create_date] , [modify_date] FROM sys.sql_logins WHERE [name] LIKE 'zmyLogin%' |

If any records return, we’ll want to use another name combination. Provided that no records return, we’ll create the six logins – notice that I’ve commented out the drop login commands, which we’ll want to run later.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 |

CREATE LOGIN [zmyLogin] WITH PASSWORD = N'zmyLogin1', CHECK_POLICY = OFF CREATE LOGIN [zmyLogin1] WITH PASSWORD = N'zmyLogin11', CHECK_POLICY = OFF CREATE LOGIN [zmyLogin2] WITH PASSWORD = N'zmyLogin21', CHECK_POLICY = OFF CREATE LOGIN [zmyLogin3] WITH PASSWORD = N'password1', CHECK_POLICY = OFF CREATE LOGIN [zmyLogin4] WITH PASSWORD = N'password2', CHECK_POLICY = OFF CREATE LOGIN [zmyLogin5] WITH PASSWORD = N'password3', CHECK_POLICY = OFF ---- Drop all created logins for testing: /* DROP LOGIN [zmyLogin] DROP LOGIN [zmyLogin1] DROP LOGIN [zmyLogin2] DROP LOGIN [zmyLogin3] DROP LOGIN [zmyLogin4] DROP LOGIN [zmyLogin5] */ |

As a note, we are intentionally not checking the password for security strength by using the option CHECK_POLICY = OFF. As a general rule with security testing, enforcing this with all logins would ensure that no one can use their login name in the password, along with requiring a minimum of 8 characters and a character combination of non-alphanumeric characters, and upper and lower case character combinations.

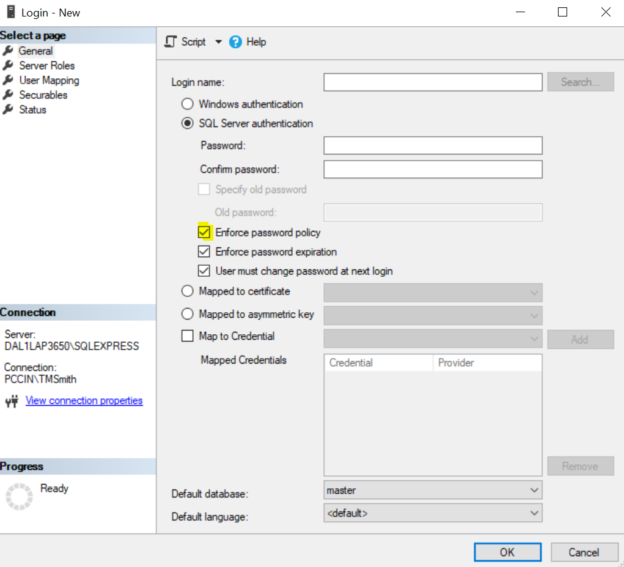

We can see the option to enforce password policy when we manually create a login through the interface or selecting this option as ON when scripting logins for creation.

As an initial audit, we can check our password complexity and see these six logins fail this requirement:

|

1 2 3 4 |

SELECT [name] FROM sys.sql_logins WHERE is_policy_checked = 0 |

Our six logins already failed an initial audit of password complexity.

Example of Security Testing against saved values

With our six logins, we’ll perform security testing with an example by checking the password hashes from the logins we created against a table with commonly used password techniques. In the first part of our example, we’ll create a table that we’ll store these commonly used passwords – in this case, combinations with login names and 1 along with the text “password” plus a numeric combination (for space, I am only iterating to 3, but it’s a good idea to check combinations of 4 characters involving ending digits – 123, 1234, etc. are very common).

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 |

CREATE TABLE tbCheck( CheckValue NVARCHAR(128) ) ----Drop table for testing /* DROP TABLE tbCheck */ INSERT INTO tbCheck VALUES ('password1') INSERT INTO tbCheck VALUES ('password2') INSERT INTO tbCheck VALUES ('password3') INSERT INTO tbCheck SELECT CAST([name] + '1' AS NVARCHAR(128)) FROM sys.sql_logins |

Keep in mind that we want to ensure that none of our logins are using these passwords. We would use this table to store passwords that have been compromised, so as new passwords are identified as compromised, our security testing would involve loading this table with these newly identified values. Next, we’ll use the T-SQL PWDCOMPARE function to return all values where the password_hash from sql_logins matches the column CheckValue from our tbCheck table. We accomplish this by cross applying tbCheck with sql_logins and comparing the password_hash column with the CheckValue column:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 |

;WITH ReturnUsedLogins AS( SELECT [name] LoginName , password_hash PasswordHash , CheckValue , PWDCOMPARE(CheckValue, password_hash) Compare FROM sys.sql_logins CROSS APPLY tbCheck ) SELECT LoginName , CheckValue FROM ReturnUsedLogins WHERE Compare = 1 |

Our results identify the login name along with the password that failed our check:

Our security testing with PWDCOMPARE invalidated these logins as using common password combinations.

In some cases, following a cyberattack, passwords are leaked and we can get a list of these passwords to check against our logins’ passwords. Following the structure that we use in the above code, we can save these passwords to a table and run a check against our logins’ password hashes. We want to ensure that no leaked password or common password combination exists, as these are known or common.

Keep in mind that even if we ensure password strength to pass this validation, there are still some combinations of passwords that are commonly used that an attacker can check periodically against our database. This is because attackers can attack at any time and can attack over long periods of time. As an example of a password that passes both security testing through enforced policy validation, in the below script, we try to create an uncomplex password that fails, but then succeeds at creating a complex password that is unfortunately very common:

|

1 2 3 |

CREATE LOGIN [zDropThisLogin] WITH PASSWORD = N'password', CHECK_POLICY = ON CREATE LOGIN [zDropThisLogin] WITH PASSWORD = N'P@ssword1', CHECK_POLICY = ON DROP LOGIN [zDropThisLogin] |

The second password passes the check policy because it meets the complexity requirements, yet it is a common password that is checked against. We shouldn’t assume that complexity only is enough to ensure the strengths of our logins. Running checks against common password combinations or against compromised passwords that are known can help us strengthen our security even above enforcing complex passwords.

Summary

We’ve looked at using the built-in pwdcompare function in Microsoft SQL Server for security testing our login passwords. This helps reduce unauthorized access that may compromise our information, intellectual property, or our design from a destructive attack. Keep in mind that using other forms of security for logging in, such as 2-factor authentication assist in reducing risks, as these work well with strong passwords to avoid unauthorized access. Password strength help, as does other methods of security.

- Data Masking or Altering Behavioral Information - June 26, 2020

- Security Testing with extreme data volume ranges - June 19, 2020

- SQL Server performance tuning – RESOURCE_SEMAPHORE waits - June 16, 2020